GenX and ’80s control culture: isn’t it ironic?

When I was at the doctor’s office a few years ago for a routine appointment, the nurse practitioner who was about my age compared being in your 40s to a “reverse” of the teen years. Instead of your hormone production ramping up, it starts ramping down, but similarly, in a chaotic way, she explained. I nodded along and thought, “Maybe for you, but not me.”

But less than six months later, I suddenly knew exactly what she meant: When my perimenopausal hormones mixed with the onset of new uncertainties about entering a new phase of life, long-forgotten teenage memories, fears, and anxieties came flooding back.

My moods were tracking alongside my two teenagers. And I was pretty sure if I had a hormone graph of my cycles, it would look like my 3-year-old son’s crayon scribbles. This intensity made me want to push at the edges, wondering and questioning everything leading up to where I was at that moment.

What did it mean to be from that last generation of women raised in the twentieth century, and how did it affect my sense of self and life choices?

My mom was on her own at 17, married, and had children young, and, like most baby boomer women, generally spent most her young adult life dealing with whatever cards life had dealt her. She was a survivor. She kept going. Though the opportunities available to my mom were way beyond anything her mom could have imagined, the opportunities for me were everything my mom could have imagined. My life could be more perfect than hers ever was.

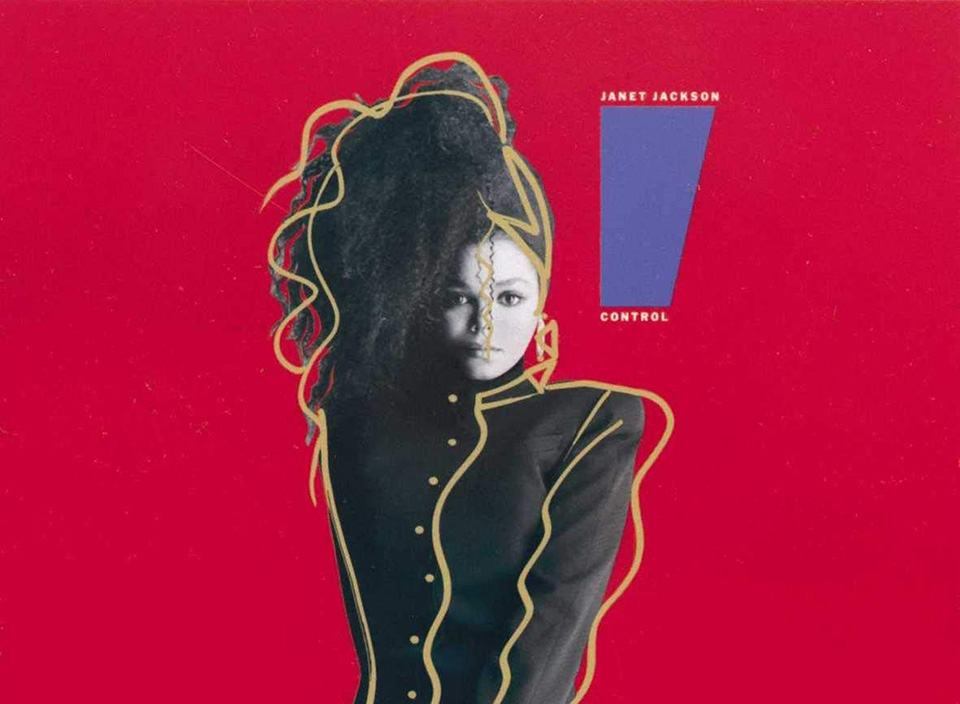

The version of the American myth for women in the ’80s stuck everywhere, from Madonna’s “material world” to logos like Nike’s “Just Do It.” The path up the meritocratic ladder was wide open. You could have it all, we were told. You could be anything. And the key to success? As Janet Jackson told us, with her sculpted hair, body, and power suit, “Control, to get what I want. Control, never gonna stop.”

Control — and, on the flip side, a lack of it — has always been a metric which women were judged writ large by society. But in the ‘80s and ’90s, with the rise of consumerism and status signaling, this message became self-defining. Social and economic limitations, along with other marginalizing factors, could all be overcome if you just tried hard enough. And if you didn’t fit into the ideal of the white, blonde, skinny career woman with 2.5 kids, a husband, and a rich social life, you’ll just have to try harder.

Body size and shape was at the top of the control list. “Now that you’re getting older, you’ll need to start watching what you eat,” my mom told me as I entered puberty. As the Chinese proverb says, she was only trying to prepare the child for the road, not the road for the child. And that road of controlling women’s bodies was the road she was on, alongside other baby boomer women. As a divorced working mother, being thin and “attractive” went way beyond vanity for my mom; not conforming to body control could literally determine her employability and financial wellbeing. I remember being 14 years old and, seemingly overnight, starting to feel the weight of other people’s eyes on my body. Open to judgment, critique, admiration, lust, and disgust. If someone didn’t like the way you looked, it was your fault. If someone liked the way you looked too much, it was also your fault.

In junior high, I used my babysitting money to buy a 13-inch cube-shaped TV for my bedroom. And I pretty much always had it on, while I did homework, talked to friends on the phone, did my hair and makeup, pushed through that final set of leg lifts. Through the hours and hours of sitcoms and soaps and dramas – I saw what was possible for me. I could have an exciting career, perfect home, family, and marriage. I could have that. I could be that. If I made the right choices. If I was disciplined. If I stayed in control. But then, the made-for-TV movies would remind me how losing control, even for a moment, might mean losing it all. The cheating husband, the diagnosis, the tragic and bizarre. And while it’s true all of that can happen, it felt like it will happen, at any moment, especially the good ones.

After the body came the conforming pressures of clothes, hair, and makeup — and another way to judge and control

The trends were quickly changing and narrow in scope. The crazy big hair and clownish makeup of the ’80s flipped to super straight hair with more precise makeup in the ’90s. The styles sold at Contempo Casuals, Limited Express, Rave, Merry Go Round, and 5-7-9 exposed more and more of our bodies, years before the internet became saturated with naked women. The sexy clothes not only drew the male gaze from peers, but also drew in the attention, and sometimes more, of much older men — and society seemed OK with this.

For straight men with relative social status, pretty much any sexual behavior was deemed acceptable. For women, however, there was this line — and it was never clear where it was — that divided the good girls from the bad. I first heard the term “date rape” when I was 17. It was like a subset, not-as-bad version, of rape. Prior to this, it wasn’t even considered rape at all. So while girls were expected to control everything, boys weren’t even expected to have enough self-control to not rape a girl.

The subjugation of women based on arbitrary beauty standards is nothing new; but what accelerated when I started college in the early ’90s was that women’s self-worth became increasingly tied to future earning power. The older Gen Xers — The Different World and Friends generation — were originally labeled “slackers,” which is so ironic. Gen Xers may have waited longer to do “grown up things” but that was because the expectations of near perfection were so high and ridiculous and across the board. To start, the pressures of having the perfect wedding became literally ridiculous in the ’90s, pushing couples to wait years, go into debt, or maybe even break up over the stress.

The controlled perfection spread to our ideas of home and cooking when I was learning to be an adult. HGTV, Martha Stewart, Bed, Bath and Beyond, Pottery Barn, The Food Network filled our heads with ideas and expectations of perfection. I think of the ’90s as the molting decade. There was more and more stuff at lower and lower prices. The containers had to become larger to accommodate the more stuff – bigger plates, bigger refrigerators, bigger houses, bigger vehicles. Controlling all that stuff was really hard. Then came the plethora of bins, containers, professional organizers, and self-storage spaces.

My first child was born in 2000, the month the human genome project results were initially released

This new age of science ushered in a new age of parenting, using ground-breaking neuroscience and advice on providing an enriched microenvironment, starting in utero. Pregnancy and the post-partum period used to be a time when you could have a break from the body control and judgment, but all of sudden, the pregnant body was also supposed to be sexy and exposed, while upholding the thin, air-brushed standards. How women got pregnant, gave birth, and fed their babies provided additional layers of control and judgment. These high standards sometimes impacted a woman’s decision on when and if to even have a child. “I need to have everything perfect and then I’ll decide,” even if that fertility window may not be open anymore.

Early internet sites and social media furthered images of oppressive perfection, giving us tips to do and stuff to buy; showing us how we too can be in control. The lists — top baby gear, Best Place to Live, Toy of the Year, GreatSchools — often changed how we felt about where we were and what we had. Maybe I didn’t even want this, even if it is “the best”? Maybe I don’t like what I have because it’s not even on the list?

I grew up in a townhouse community 20 miles outside of Chicago. In that two-block radius lived people from all over the world, all over the country, and within every socioeconomic class. That rarely happens anymore. During my adulthood, I saw the bifurcation of society happen in real time, dividing groups based on background and credentialing. College grads marrying college grads produced the new power couple, fueling the information economy.

One group moved into bubbled zip codes where everything was precisely controlled, while people with fewer securities felt more marginalized, less appreciated, less seen, and even resentful. And why wouldn’t they? And that “they” was my family a generation ago, people I know today and will know tomorrow, maybe myself. Having spent my adult life in a controlled bubble, I have to wonder how I’ve contributed to the divisions today. Complying was perpetuating, even if I was unaware.

And isn’t it ironic? Don’t you think?

I listened to Alanis Morisette sing over and over when I was in college. And now 25 years later ask the same damn question. I’m finally realizing my body was totally fine, as awesome as every woman’s, just as it starts morphing into who knows what. I’ve reached that place that I thought would bring security, but what does that even mean anymore? I spent so much energy worrying about things that never happened, and feel unprepared for what has. I prepared my kids for a world that is fading, and can’t see what comes next.

The crapshoot world of today is scary. The shifting sands make it almost impossible to feel grounded or prepared, but there is also tremendous relief that finally, FINALLY, the repressive control is lessening for many women and marginalized groups. This brings a freeing, and maybe leveling too. There is not one singular definition of success, one beauty standard, one life path.

“As I move through my middle years and learn to let go of more things more often, both by choice and necessity, I realize that control itself wasn’t the problem. It was the idea that total control was even reality-based and that it was layered on top of a set of performative, outcome-based standards that inherently excluded almost everyone.”

As I move through my middle years and learn to let go of more things more often, both by choice and necessity, I realize that control itself wasn’t the problem. It was the idea that total control was even reality-based and that it was layered on top of a set of performative, outcome-based standards that inherently excluded almost everyone. Never asking for what I wanted or needed. Feeling my worth was tied to how I looked, how hard I worked, and who I cared for. Not even knowing my boundaries, much less being responsible for them. Apologizing when I didn’t need to.

It can be easy to cling even tighter to these known patterns when the body starts preparing for menopause a decade or so before it happens. But when you start to let go of these patterns, you can start feeling a curiosity, confidence, and connectedness to a broadening space. In this space, the why I’m doing something is beginning to have more salience than the what I’m doing. As I let go of the control ideology that shaped my early life, I have to think, now is a pretty awesome time to become an older woman.

Credit where credit is due: You probably already know this, but the top photo is Janet Jackson’s third album, Control (A&M Records.)

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Amber

Fantastic article, thank you!

jackie ghedine

This is an excellent article, thank you for putting it into the world. Keep sharing these Gen X perspectives and stories, they need to be told.