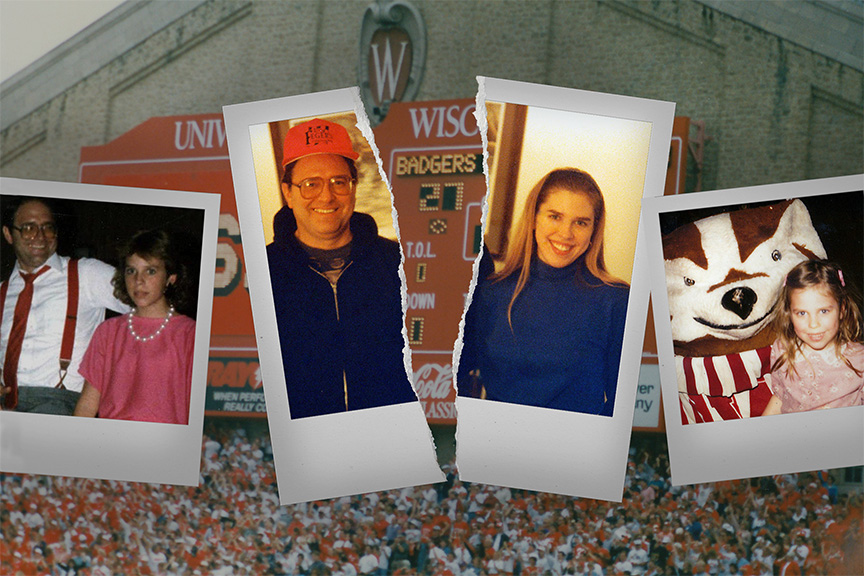

Feeling badgered by past family trauma

A few years ago, my family and I moved to the suburbs of Madison, Wisconsin, a city that holds special significance to me. It’s the place where my parents met, where my dad went to college, and where I had visited many times with him.

Initially, I loved exploring all the new places to go and things to do. But then I kept seeing these damn UW Bucky Badgers all over the place — sorry fans. The cheeky red and white mascot really started to bother me with its puffed-out chest, fisted hands, angry face, and sharply clawed feet. To me, the emblem didn’t just represent the college. It was also a strong reminder of my dad. Not the pleasant-to-be-around “fun guy” side, but the other one — the win-at-all-cost, always right, “you’re either with me, or against me” side.

And because my dad died suddenly a decade earlier, these feelings of resentment were buried under layers of sadness and grief. Feelings that went as far back as I can remember, during intense periods of conflict between my parents that led to a divorce where choosing sides was the only option. I chose my mother’s side, which, emotionally, was my only option. But this choice came with a cost — the loss of loving my father, and feeling loved by him. And all of these conflicted feelings felt frozen in a state of saturation, with nowhere to go.

Sixty-some days after my dad retired at the age of 60, I got the call that he was gone. Just like that. No warnings. Just gone. It was the first day of December, the first snow of the season and just after the first Black Friday that my dad didn’t work during his nearly four decade career in retail management at JCPenney’s.

Initial shock was followed by a strange and guilty feeling of relief: The loyalty tug-of-war between my divorced parents that persisted for many decades was finally over. I wouldn’t have to hear him utter the phrase “your Mother” as if it were a swear word. I would no longer hear his booming voice on my answering machine commanding me to pick up the “[insert expletive] phone.” I wouldn’t have to stress over making plans with him because I could never be sure of the mood he’d be in that day or where my tolerance level would be.

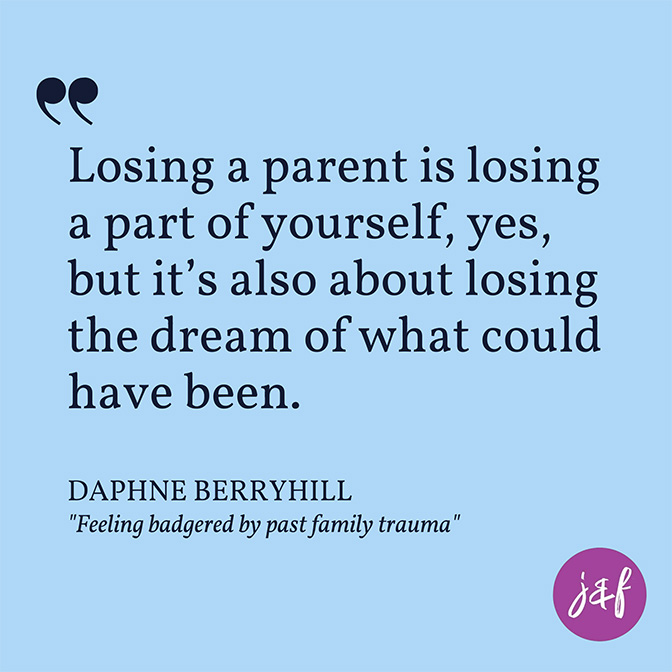

But then the reality set in, and it brought me to my knees in sorrow. The deep sense of loss pulled my entire body to the floor, literally. Losing a parent is losing a part of yourself, yes, but it’s also about losing the dream of what could have been. While I generally maintained a “nice” relationship with him, I had always hoped for deeper reconciliation between us. That hope felt unfairly taken away.

During the months that followed, I cried — at random times and at purposeful ones — while I listened to Bread sing, “I would give everything I own / Just to have you back again / Just to touch you once again.” I love that song, because it really captures the true depth of grief. Within a few months, I closed the floodgates of sorrow and trudged up the hill of building my life amidst many changes on the horizon: new children, jobs, and houses.

Conflict was an all-encompassing narrative of my childhood

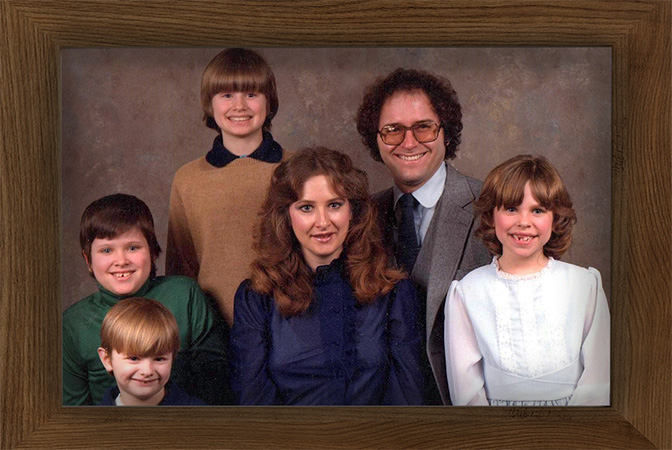

I grew up in a two-bedroom townhouse in Suburban Chicago. My dad worked in management at JCPenney while my mom worked data-entry overnight jobs, later building a career as a technical recruiter.

My parents’ lists of stressors were long: having four children by their mid-20s, a special needs child with Spina Bifida, inflation despite double-digit interest rates, no extended family nearby in a “it’s all on you” responsibility culture, no examples of how to share decisions and household responsibilities, and growing expectations of both fulfillment and material success. And underneath these surface struggles lay their conflicting motives — my dad’s desire for hierarchical success and my mom’s need for emotional attachment.

Many of my earliest memories involve some random act of anger

My dad throwing a plate of spaghetti at our TV or breaking my bedroom door down to pull my mother out of the room where she was hiding. Me wondering if a sound during the night while I lay in bed was just the start to another explosive argument. Would the police come again? What would I tell my friends walking to school the next day? Of course, there were plenty of good memories as well, but because the conflicts were so unpredictable and so extreme, there was always a cloud of chaos overhead.

During an argument between my parents, I would try and listen, to figure out why they were fighting, but I never could understand exactly. Most likely, why they were fighting had to do with so much more than what they were fighting about.

The month I turned 9, my parents told me and my three brothers they were getting divorced. At that point I realized that within their marriage, a conflict environment would always be present. But I hopefully wondered, maybe it would end if their marriage ended too.

For more than a year during my parents’ divorce, they continued living under one roof

The high conflict got even higher. Meetings with lawyers, fighting over big things like custody and random things like Polaroid pictures and cheaply made ’70s stuff. One time, our cat disappeared for a day and there was actual fear that my dad may have taken her out of revenge. Though I was relieved to find her curled up in a corner, the idea of someone so close doing something so hurtful persisted. My dad hired a private detective to follow my mom’s new boyfriend, a jovial, much older man with an interesting past who struggled with alcoholism. I constantly feared that I might say the wrong word to the wrong parent and make things worse.

Meanwhile, I focused on performative success — Trapper Keepers filled with pages of perfectly completed homework in bubbly cursive, staying on beat and in form during dance class and memorizing each word in an expanding list of Catholic prayers. And at 10, I found a new way to separate myself from the chaos at home — teen culture. Out went the Barbie Doll Dream House and Cabbage Patch Kid dolls; in came the boom box blaring music from Chicago’s B96 and teen posters from Tiger Beat magazine. I could gloss over the pain with a new cherry-flavored tube of Wet ‘n Wild. Valley Girl–speak allowed me to preempt any question with an “I don’t know and I don’t care” nonchalance. And perfecting the Molly Ringwald head tilt and eye roll further protected me from caring, while being totally unaware of how this might be deserving of a “stuck-up” label.

During the divorce period, my dad’s outbursts of anger worsened. I was learning about the changing mores through watching ABC Afterschool Specials and waking up to Oprah on summer mornings, but there was a long lag before most adults moved past the “spare the rod, spoil the child” mindset.

After the divorce, our family drifted into sides

My oldest brother stayed on my dad’s side, where he could go and live with our grandparents in rural Wisconsin, getting away from it all. As hard as it was living there, helping out while my grandfather was dying, he could find moments of quiet peace away from the chaos, connecting with the older generations.

The first Christmas I spent with my dad after the divorce, he called my mom a whore, prompting me to walk out, walk somewhere, ending up in Dunkin Donuts making a collect call to my mom. By the time I was 13, there was a moment when I made a conscious decision, which was more of a realization. The only relationship that I could have with my dad would be at a distance, I told myself, and with limited depth. As my dad followed his JCPenney career with several moves throughout the Midwest, we drifted further apart.

My other brothers and I stayed with my mom, on her side, moving to what felt like another world, but was just a split level on the other side of town. My mom married her boyfriend who was soon diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver, sadly dying a handful of hard years after that. With my mom being overwhelmed, striving to maintain her career and sanity through this time, always wanting to say yes and too tired to say no, the frequency of guilt trips to the many nearby shopping malls became an increasing habit, going into every store except JCPenney.

Each new style became a new way of showing people that I was like, totally OK — off-the-shoulder jerseys over zippered parachute pants, studded blouses gathered at the waist with slouch belts, Guess jeans folded then rolled at the ankle, oversized color-blocked Esprit sweaters over stirrup pants, chunky plastic and metal earrings from Claire’s, sometimes worn only on one side, boots laced up over my ankles and my wrists covered with a Swatch watch or an infinity of jelly bracelets. And then came the final layer of protection — countless pumps of Rave Ultra Hold Hairspray and Ex’cla.ma’tion perfume — and I was ready to face the world.

During the early days of the pandemic, when things were still and I was home, I began having long conversations with my oldest brother Patrick.

We were separated by our parents’ divorce, on opposite sides, and only decades later began sharing our different perspectives. For the first time in my life, I began to have some grasp on what my dad was thinking and feeling. Why was he so afraid of letting me see him, really see him?

As I became more curious, I pulled out letters that my dad wrote to my grandmother many years before. One letter my dad wrote to his parents when he was working his first job showed me how scared and vulnerable he felt. He practically begged his parents to buy items from his JCPenney department, listing in great detail possible items that might interest them, like fondue pots and ice buckets, along with the corresponding catalog pages and prices. With a family to support, he was so fearful of being fired if he didn’t sell out that holiday season.

While it was clear from my dad’s letters that he felt more complex emotions than the extremes that I remember him showing — especially feelings that accompanied vulnerability — he lacked both the self-awareness and emotional language to express them. Many of the people closest to him suffered from this shortcoming, but I began to appreciate how much he suffered from it too. Learning more about my dad’s perspective gradually softened my own tribal mindset, and letting go of this initially left me feeling alone in myself.

Being forced to really look in the mirror resulted in multiple “Oh shit!” epiphanies. Like him, I too had a tendency of filling up too much space in my relationships, crowding out other people’s thoughts and feelings. Like him, I could come up with ten reasons in ten seconds why I was right. And at times, I was also hyper-focused on a goal and ended up overlooking something — or someone — more important. I had anger issues too — but mine went inward rather than outward, as is more common with people socialized as female. And when I was able to see this, I was able to uncover the “understory,” the real story that explained our motivations and role in conflict. (Amanda Ripley coined this term in High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out.) And the understory to our behaviors was fear: the fear of fully being seen. We may have armored up in different ways, but we both used armor to conceal our vulnerabilities.

From the moment my husband met my dad in 1993, he could see my dad. Not the Bucky Badger persona, but the vulnerable man underneath, probably in the same way he could see my vulnerability too. Why did it take me so many years to see this? Why is it that a total stranger can sometimes see the people we’re closest to better than ourselves? Maybe my dad’s persona bothered me so much because it reminded me of what I didn’t want to see within myself. Why are we so bothered about behaviors we see in others, while being oblivious to our own?

There is no singular story that can explain my dad. There is not even a story that one side can tell at one moment that would hold up through time. There are lots and lots of stories — none completely overlap and some have no overlap. And the most surprising thing I’ve found coming to terms with this is how beautiful and interesting this complexity is. The one thing I know for certain though, is that my dad loved me just as much as I love my own kids. And I also know that the best way I can honor his memory and show my love for him is to allow my own vulnerability to be seen in ways that matter, and to allow safe space for others to share their own vulnerabilities too.

When I see a picture of my dad, or a UW Bucky Badger for that matter, I’m beginning to feel something other than triggered memories from long ago. I see a reminder of how bittersweet love and time are. I see a reminder of how dangerous bravado and hubris can be when they’re misplaced outside of a sports arena. And I see a way out of conflict and into better relationships, through letting go of fear and shame, showing vulnerability and being open to new ways of thinking.

Top photo illustration by Konrad Berryhill