How I coped with chronic trauma from growing up with undocumented parents

Anytime I’m in a grocery store, at a bakery, or in a restaurant and I come across strawberries, I think about my hometown. Watsonville, California, looks like old pickups on the side of the road packed with berries and smells like fields and fields of apples. However, fresh produce isn’t the only thing that reminds me of home. I left when I was seventeen, leaving behind an anxiety-ridden childhood marked by the loss of my father, my mother’s depression, and my inability to make sense of either. Then, there were the shared traumatic experiences between peers; things like gang violence, alcoholic parenting, and general physical and emotional abuse. Whenever the topic of immigration comes up, I’m immediately five years old again, worried about my parents’ legalization in a country that denies it to some. Home has always been a mixed bag.

When I landed in San Francisco after leaving the farming community that raised me, I took a big exhale. The type of anonymity that a big city provides was what I needed at the time. Now? I understand intellectually why I left my hometown, but my heart never left the Mesa Verde neighborhood at the end of Green Valley Road in Watsonville, CA.

What was hard about my hometown

Growing up in Watsonville was difficult on a few different levels. Let’s talk about acute trauma, because it does not mean minor trauma. It means a singular event like the Loma Prieta Earthquake of 1989, which happened during game five of the World Series when the Oakland A’s and The San Francisco Giants went head to head.

Parts of the Bay Bridge collapsed during that earthquake, and parts of my hometown burned to the ground. The movie theater where I had watched E.T. for the first time crumbled like papier-mâché. Many neighborhoods in the Bay Area and throughout the Central Coast were demolished in seventeen seconds flat. This experience created shared trauma within my hometown community that has stayed with me into adulthood.

While that single event changed my life, it was the chronic trauma and complex trauma of growing up with undocumented parents that began to shape my anxiety. If you grew up worried about personal or parental legal status, you’ll know what it feels like when a police officer pulls you over, and your parent’s green card is in the mail, or todavia no llega (has yet to arrive). You know what it’s like to listen to a conversation about immigration from people far removed from the ramifications of being on the opposing end of political power. If this is also your experience, we have a shared chronic trauma and I see you.

Chronic or complex trauma changes your DNA. It affects the way you move through the world, and yes, it makes anxiety a regular part of your life. Knowing which type of trauma you have is crucial. Once I separated my feelings of anxiety over natural disasters from those that come from complex trauma, I could wade through the noise. Therapy. Therapy. Therapy.

What it was like to build my own home after leaving

When I left my hometown for San Francisco, I took a big exhale: I’d created space between those bad experiences and myself. Ten years later, I had a social circle in San Francisco that knew me. Friends who I loved and love still. I was part of a community that nurtured and cared about my wellbeing. When I left my hometown, it was exciting when I walked into a room full of people who knew nothing about me. Now at 41, I find it exhausting. All I want in the world is to be around people who know me; my struggles, successes, children, and journey.

Recently, I’m also discovering the long-term impact of leaving parts of myself—of my trauma—behind. When I left Watsonville, I no longer talked about things like losing my father. But, in trying to lessen my grief, I left a piece of myself. I left the suffering that was a part of me. In short, leaving my hometown because of what it represented did not work.

How I forged a new relationship with my hometown

Over the years, I found myself putting my hometown on pedestals: some tragic, some glorified, all fantasy. That began to change in 2019 when my five sisters and I decided to start a nonprofit benefiting first-generation or immigrant students from the Central Coast. Each of my sisters and I had left town in the ’80s and late ’90s. We returned full of presumptions. We wanted to give back, but where was the need? We had no idea; we just had our memories, and well, our personal anecdotes.

One of the biggest things I’ve learned about the work we’ve done so far has been about the wide gap between the hometown in my mind and the actual hometown of Watsonville that exists today. Part of our scholarship-building effort has involved interviewing people in Watsonville who are positively impacting the community today.

Recently, I interviewed a friend and Watsonville police officer, Juan Trujillo. He shared a video with me of a Watsonville cop talking to a farmworker in town. The cop in the video said, “My parents were farmworkers; this is my community too.” I fell apart. It never occurred to me that cops—the ones I feared as a kid—might have also been raised by farmworkers just like me. In my mind, the cops and La Migra (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE) were the same. It has been such a blessing to throw out the old script and insert the reality of what Watsonville is like now. Building this scholarship has healed me.

Here are just a few beliefs that have shifted for me in doing this work:

- Small towns are the original small business. More than likely, someone from your hometown has started a company that you could be supporting. Find out what they’re selling and buy it!

- Get past the idea that you’re an outsider because you left. Join a board, a committee, or support your hometown in any way you can. Home is still there, ready and willing to accept your help.

- Re-evaluate the embarrassing experiences in your mind that are keeping you from donating your time or money. Nobody cares that you wore your sisters’ clothes well into high school. Chances are nobody remembers what you think was traumatic.

- Some of your hometown friends did amazing things with their lives—and they never left. Join them!

- People from your community have shared memories with you—memories outside of trauma! For instance, there’s that kid who remembers the real story about the scar on your forehead. It was that time you both ditched school, and you tried to pierce your faces with a needle and thread. GOLD!!

What it means to return home after a long time away

Part of returning is about healing and about remembering the positive things that made you who you are today. It’s about sharing newly found success, like kids getting into college or an old friend starting a new business. Rewriting the script and creating new memories on old streets has been exactly what I’ve needed at this stage and age in life.

Last week while driving through my hometown, I was able to see the beauty. Even after 22 years of living in the Bay Area, there’s something about the rolling fields of produce along the Central Coast that feels like home. The stand that our family used to buy veggies from is still there. The church that crumbled during the Loma Prieta Earthquake in 1989 was rebuilt, and the movie theater where I saw E.T. for the first time is now a furniture store. It’s still home. I am grateful to be able to rewrite the shared trauma into shared joy.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Shawnte Fernández

Growing up in Watsonville this hit home. Thank you for providing space to talk about trama and how we can make a positive impact. My grandfather in fact was a farm worker turned entrepreneur he owned 200 acres of Strawberry Fields in Salinas. I felt like I was always running away and now as an adult like you I am learning to appreciate the good. Keep up the amazing work xoxo

Olga Rosales Salinas

Watsonville, Salinas, Castroville… all of the central coast is so incredibly special. We’re so lucky to have grown up there. Just like you, I didn’t realize how special it was until I left.

Thanks for reading Shawnte!! xoxo

Brisia Rodriguez

This piece really made me reflect on the good things and experiences we have in our lives and we don’t even know because they are still overshadowed by trauma.

Thanks for sharing.

Olga Rosales Salinas

Watsonville, Salinas, Castroville… all of the central coast is so incredibly special. We’re so lucky to have grown up there. Just like you, I didn’t realize how special it was until I left.

Thanks for reading Shawnte!! xoxo

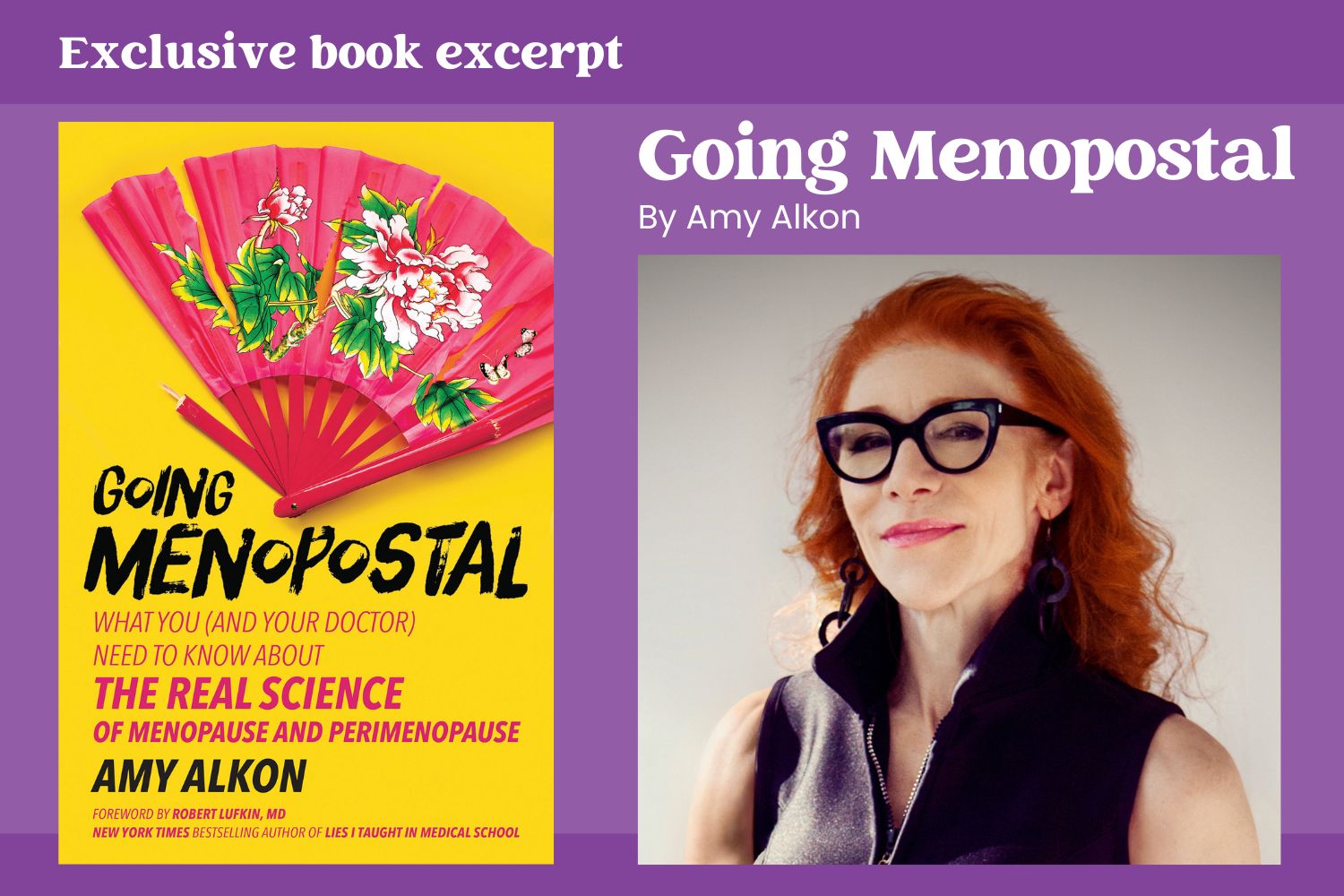

Pingback: Well Woman Weekly: Amy Cuevas Schroeder on Perimenopause and Parenting - Blood & Milk