Empathy for the midlife-crisis man?

As a child of the ‘80s, my understanding of a midlife crisis was largely formed around the character of Clark Griswold. The bumbling patriarch of the National Lampoon’s Vacation movies, Clark was a man whose outsized expectations of life rarely conform to reality.

Despite a trusty corporate salary, a house in the suburbs, and a secure place in America’s middle class, Clark was always chasing a version of perfection that remained just out of reach. His attempts to engineer idyllic family experiences and cherished memories inevitably failed, leaving his wife and kids to treat him with a kind of bemused tolerance.

To cope, Clark would sometimes escape into little pockets of his imagination where, instead of a beleaguered family man, he was being seduced by a shopgirl, or riding shotgun in a Ferrari with Christie Brinkley. Clark never came across as lecherous or predatory in his fantasies about young women. His little fantasies read as mostly harmless — the pathetic yearnings of a hopeless buffoon.

Clark is just one instantiation of a tragicomic trope: the American male in midlife.

The cultural landscape is littered with examples, ranging from darker instances, like Kevin Spacey’s character in American Beauty, to parody, like the husbands of The First Wives Club. But growing up with repeated exposure to the theme, it seemed to me that the common thread weaving through the narratives was the fundamental inability of men to accept the fact of aging. Like Clark, they’re all clinging desperately to youth, attempting to escape reality through younger women and sports cars.

I rolled my eyes for decades at the absurdities of middle-aged men.

The bell tolls for me

That is, until my biological clock struck the halfway mark and my own absurdities pulled up alongside me. But instead of Christie Brinkley in a Ferrari, it was Jeremey Allen White on a fixed-gear bike — or, occasionally, Timothee Chalamet on a sandworm.

Suddenly, I was consumed by some pretty baroque thoughts about who I would consider to be much younger guys. Guys who, although fully formed human adults, have probably never manually rolled down a car window or dialed a rotary phone. And though the age difference might not relegate me into old-enough-to-be-their-mother territory, I’m definitely old enough to have been asked to babysit.

Finding myself fantasizing about younger guys was startling not just because it placed me on the same sad plane as Clark Griswold, but also because I’d previously always been attracted to older men. I spent the entirety of my 20s in relationships with guys who predated me by at least a decade, and I reveled in the role of ingenue, eager to sit at the feet of a dashing sophisticate and lap up knowledge of the wider world. Looking back, it’s clear that I believed they could offer me some kind of shortcut to evolution – a direct path to my highest self.

Although it was definitely misguided, there was nothing outwardly wrong about me dating older guys. The age gap between older men and younger women is so thoroughly normalized in our society that we even have a charming little term for it to dispel any potential ick: a “May-December romance.” No one bats an eye when a celebrity like Alec Baldwin or Brad Pitt hooks up with a woman from the May category, even when the age difference is approaching 30 years.

But like so many patriarchal standards, it doesn’t work both ways. Of course, women can and do pair off with younger men, but it’s much more of a cultural oddity. When a 41-year-old Demi Moore married a 25-year-old Ashton Kutcher in 2005, the world went bananas. And lest we think we’ve somehow evolved, Heidi Klum’s 2019 marriage is rarely referenced without mention of the fact her husband is 17 years younger.

All of this to say that my sudden fantasies involving younger men – one of whom barely looks old enough to vote — came freighted with a lot of psychosocial baggage. And as a chronic over-analyzer, I couldn’t stop interrogating myself over what these thoughts could mean. Was I unhappy in my marriage? Was I bored with my life? Had I developed a sudden kink for hot rodent boys?

What the fuck was going on?

How U doin’?

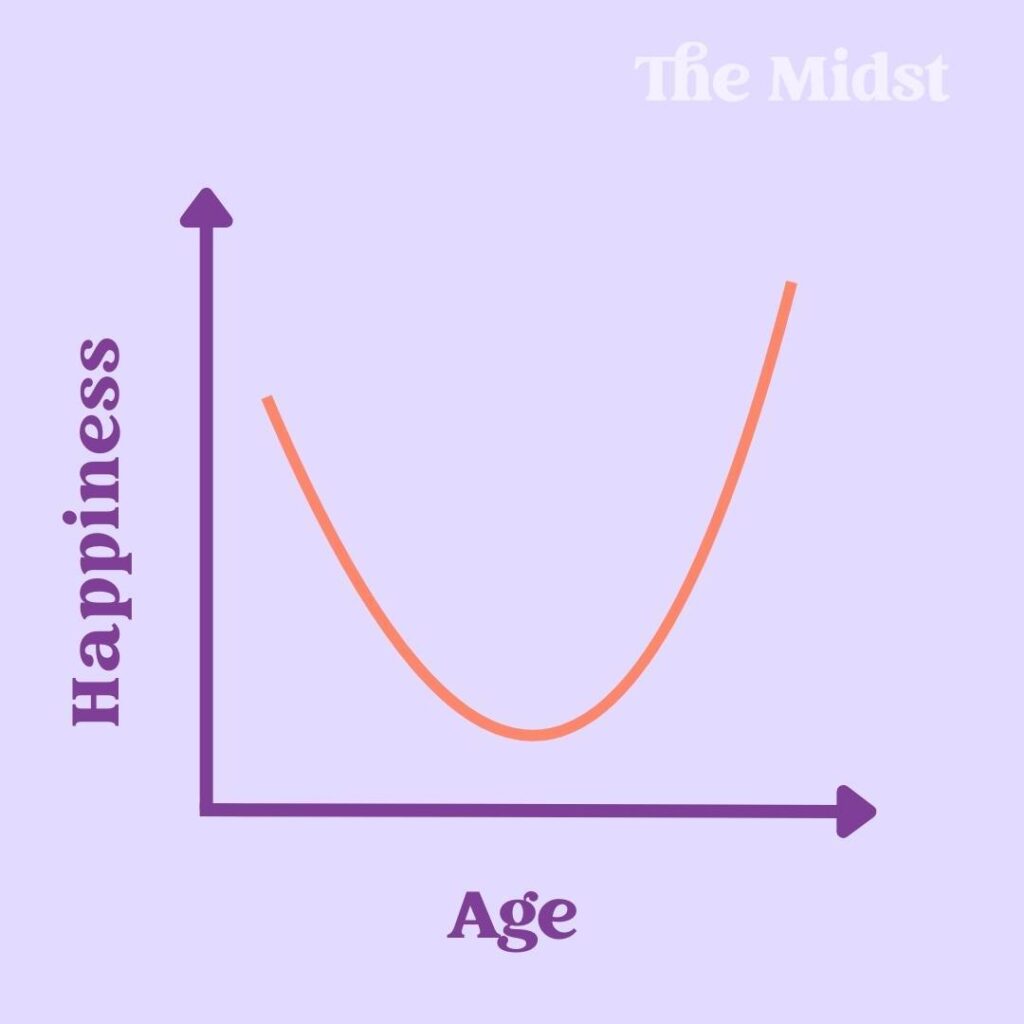

According to some studies, happiness in life tends to follow the bend of a U-shaped curve. It starts off high, but by the time we hit our 40s, we’re approaching the bottom of the U, where we’re left to wallow in the depths of dissatisfaction. Then as we move past midlife and into our sunset years, the U bends back towards happiness, eventually establishing us somewhere near where we began.

The theory has its detractors and a U-curve is certainly far too simplistic to describe the arc of all human existence. But as a visual reference for understanding my own experience, it comes in handy.

Because like a lot of women in their mid-40s, I am barely holding my shit together. The past few years have felt being pelted from all sides in a game of existential dodgeball.

I’m part of the squeeze generation, which means that in addition to a young child, I also have aging parents whose health I worry for and whose life decisions I question daily. (As in, no, you should NOT continue to feed nine feral cats, and yes, you SHOULD downsize to a home that isn’t a multilevel Victorian death trap.)

At 46, I’m experiencing the lowest career satisfaction of my professional life, partly because I’m constantly negotiating the incompatibility of childcare and full-time work. Money, which I assumed would be kind of magically sorted out by now, is a constant, looming concern.

I’m fortunate enough to have an amazing husband who I truly love, but I rarely have the time or inclination to focus on our sex life. And that must frighten me on a very deep level because I have a recurring nightmare in which he leaves me and I can’t figure out how to download Tinder.

On top of it all, I am perimenopausal. Hopelessly, ferociously, terrifyingly perimenopausal. So much so that until making the fraught decision to begin HRT three months ago, I was dealing with a brain fog so debilitating I could often not immediately recall my own last name.

And it is here — in the midst of all this shit that I would consider very centric to the experience of modern womanhood — that I began to develop a certain empathy for men.

Hear me out.

Midlife fails the Bechdel test

When it comes to the popular conception of the midlife crisis, men have long been the butt of the joke. According to the narratives I grew up with, men are the only ones struggling in midlife while women are relegated to minor characters in the scene.

But man or woman, we’re all languishing down in the bottom of the U-curve together. The idea that we would be having radically different reactions to this time of life simply doesn’t square. It’s rough down here. And now that I know that,

I don’t feel great about my participation in reducing a man’s experience of midlife to caricature.

To be clear, my point is not that we should be devoting any more of our emotional resources to developing a deeper understanding of men because, frankly, that’s what the whole of human history has already been about. And it’s precisely because history has been centered around the male perspective that when we think about midlife — a time men and women occupy in fairly equal measure — we almost always think about the male experience.

In a culture that feels free to poke fun at the male midlife crisis, it’s easy to overlook that women are experiencing something similar. And being excluded from that narrative, no matter how reductive or harsh it may be, is ultimately to our detriment. Because it stands in the way of our understanding of a fundamental part of ourselves.

If, during my formative years, there had been a female analogue to Clark Griswold, maybe I would’ve developed a sense of levity around female aging. If I’d inhabited a cultural landscape in which female characters were allowed their own spectrum of experiences in midlife, maybe I would’ve experienced less shell shock upon arriving here myself. Because even movies as silly as National Lampoon’s carry a cultural weight. The media that surrounds us as we grow exerts an ambient influence over who we become.

Case in point

Maybe if I’d grown up with a better understanding of female desire, I could engage in healthy sexual fantasies without spiraling immediately into guilt and shame. But instead, a typical “fantasy” starts off with me shoved up against a dumpster by Carmy Berzatto as we make out in the alley behind his restaurant. So far, so good. Who doesn’t love a good fantasy centered around the tortured titular character of The Bear? But before I can even get my imaginary hand down Carmy’s imaginary pants, I stop.

How exactly is this happening? I ask myself. How am I just hanging out in an alley at 1 a.m.? Who put my child to bed? Am I cheating on my husband? I would never cheat on my husband. So, does that mean my husband’s dead? OH MY GOD, AM I FANTASIZING ABOUT MY HUSBAND’S DEATH?

Of course I’m not. And in my rational mind, I know that. But I’m so bound to my identity as a wife and mother that I can’t escape it, even in my own fantasies.

Yet I really, really wish I could.

Because the pressures and responsibilities of midlife require the occasional escape from reality. At this stage — and maybe especially as parents — we’re all grappling with the constriction of possibility. It’s not just that our worlds have become smaller, it’s that our choices have narrowed, making even our possible worlds seem smaller. And confronting that reality can occasionally fucking suck.

Acknowledging that it can suck doesn’t mean that I’m a bad mother, or an unfaithful wife. It doesn’t mean that I don’t love my life.

I can have a fantasy that has nothing to do with actually wanting to fuck a young, emotionally unavailable chef in a filthy Chicago alleyway. It’s just a means of reconnecting with a past self who could afford to make those kinds of mistakes. It’s nostalgia for a time in my life when nothing was fixed and everything felt possible.

Which is not to say that there are any circumstances under which I would want to trade my present reality for the angst and misery of my 20s. Sometimes it’s just nice to imagine myself back there for a while — kind of like having a quick drink in a dive bar.

I’m OK – You’re OK

But none of these realizations have come easy (no pun intended). And every time a tousled young Chalamet comes bursting through the sands of my subconscious on a sandworm, I reflexively shut those thoughts down.

Lately, I’ve been trying to give myself permission to lean into these odd midlife developments without judgment. Maybe that would be easier if I weren’t steeped in a culture that reduced men’s midlife experiences to a punchline, or refused to acknowledge that women have any experiences in midlife at all. But here we are.

So I think it’s important to put my own absurdities out there into the ether. Like, “Hi, I’m Sarah. I’m navigating a really weird time in life and I’m getting through with a little help from my hot rodent friends.”

There’s no shame in that.

In this burgeoning effort to develop some empathy for myself, I’m trying to extend it to others who might be travelling the same road. That includes someone like Clark Griswold who, at the end of the day, is just a dude at the bottom of the U-curve, trying to do his best. So go ahead, Clark. Enjoy your time with Christie Brinkley. I see you, and I wish you well.