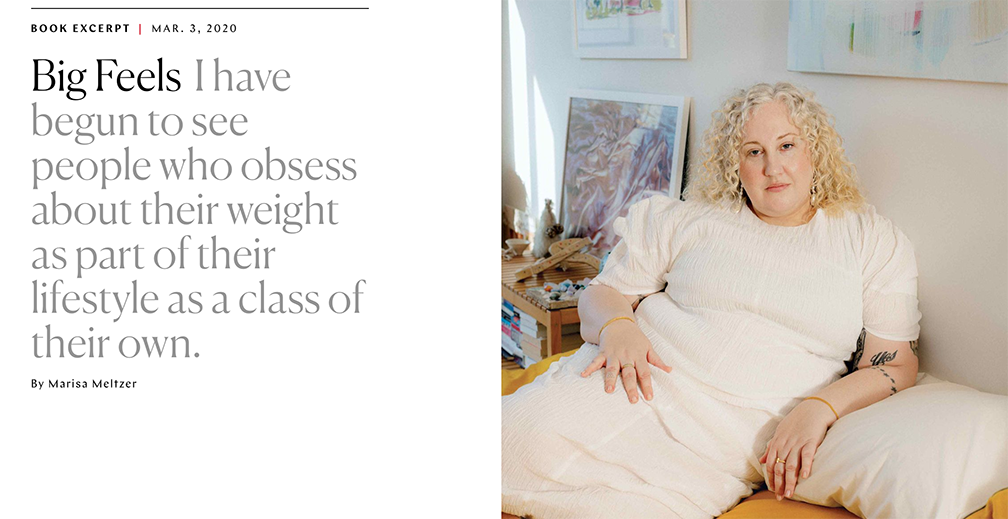

This book is a big deal in a world of thin people

I live in a world of thin people. I interview the famously thin — actors, models, musicians, influencers — but mostly I observe them. I know their habits, but I’m also aware that I am not one of them.

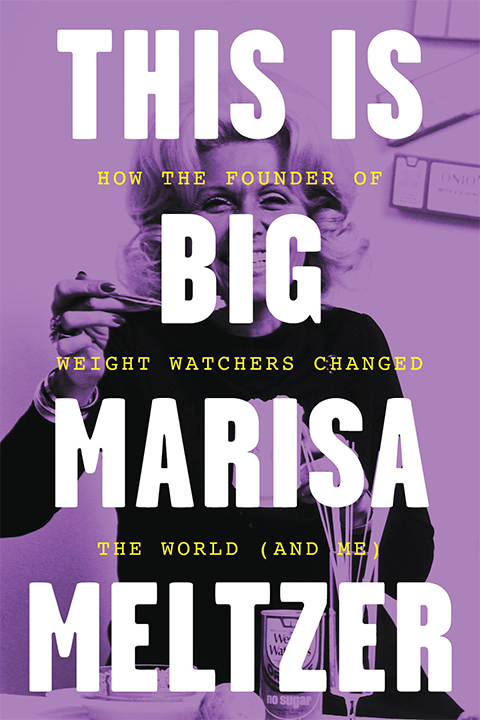

That’s a slice of Marisa Meltzer’s third book, This Is Big: How the Founder of Weight Watchers Changed the World—and Me. The book tells the true story of Jean Nidetch, who overhauled her life from a frustrated housewife to pioneering weight-loss entrepreneur before she died in 2015. But this is more than just Nidetch’s biography. Stylistically similar to Julie and Julia, Big is also Marisa’s story as a lifelong dieter who struggles to make peace with her weight. Marisa documents a year in her life on the Weight Watchers program, while weaving in the history of Nidetch’s business-building journey.

You might know Marisa’s work from the Me Time column in The New York Times, her Roxane Gay profile for Elle, or her Busy Phillips story for the New Yorker. She’s a brilliant writer, a former riot grrrl, a Brooklynite from California, and as much as she disagrees with some of Jean’s rigid philosophies, sees a bit of herself in the dieting mogul.

If I remember right, I met Marisa nearly two decades ago, when she owned a clothing boutique in San Francisco. I was producing the first “fashion photo shoot” for Venus and we needed clothes. Marisa kindly shipped a box of stylish stuff made by independent designers for our staff, who doubled as “models”. We stayed in touch when she later moved to New York, and began crafting her impressive writing career. Marisa wrote the “Style Idol” column for Venus, and in 2007, we talked on NPR for How Sassy Changed My Life, her second book that she co-wrote with Kara Jesella. Fast-forward eight years to 2015: I had two babies in one go, and as new parents do, lost touch with Marisa. When I heard about This Is Big, I reached out to set up an interview and devoured an advanced copy in chunks when I could get a babysitter.

This is a healthy slice of our conversation from February 2020, before the pandemic hit the States and before the world has access to her book. At the time that we talked, she was in “the weird in-limbo state, when you’ve finished something but it doesn’t quite doesn’t belong to the world yet.” Marisa talks about “confident vulnerability,” her inability to make peace with her body, and how she’s at the age where she’s wise enough to not take shit from anyone.

How does it feel to completely open up to the world about your struggles with weight loss?

I’m still processing my feelings about people reading the book. It’s honest and raw. It was important to me to be really honest. While writing the book, I kept thinking, “I can edit this stuff out,” but it didn’t feel right. I’m a bit nervous but also excited. This is a book about weight loss, dieting, and body in a way that hasn’t been talked about before. There are a lot of people like me who’ve been many different sizes and who have similar histories.

People who know me well and read This Is Big said there was so much they didn’t know about me. It’s not because I don’t trust those friends with my feelings. How often are you like, “Let’s sit down and talk about the things I’m most uncomfortable talking about”? I see my friends rarely enough. As you get older and have more responsibilities, you don’t see your friends in person all the time like in college.

When I see my close friends, that time is precious. I’m probably not going to interrupt and say, “Hey, can we talk about junior high for a while?” It’s not a super fun place to think about. I understand why it was news to them — these things just don’t come up; they live deeply within you.

I’ve become what I call “confidently vulnerable” in my 40s. I’m talking about my problems and flaws as if they’re a gift. Do you feel like you’ve gained confidence in being vulnerable?

I’ve written personal things for years. My vulnerability has changed with age. There’s a lack of vanity, and there seems to be less strings attached. As I age, I’m better able to get to the heart of what I’m talking about. There’s something about aging that makes you vulnerable — especially in your 40s.

Aging seems like an abstract thing for most of your life, with so many jokes and cliches. In my early to mid 30s, I began noticing that I was aging. Fine lines were the first indication of, “Oh, my face is aging. I’m getting older.”

Around 40, I started feeling changes in my body. I broke my ankle when I began writing This Is Big. Healing was really hard — even in the way my body felt after healing. The cast has been off for almost a year and half, but I still feel asymmetries. I feel a little off.

I experience perimenopausal symptoms. I’m 42 — very much in the perimenopausal age range — and I got an ulcer recently. All of these things made me think, “Wow, this is happening.” It’s affecting me.

I showed up sweating for a fancy magazine interview, thanks to perimenopause, plus it was a really humid day. An assistant set a box of paper towels next to me while I was doing the interview. That made me feel really vulnerable. Maybe I’m more at ease with being vulnerable and I’m becoming more comfortable.

At the same time, I live a pretty youthful life for someone in their 40s. I’m pretty free and live in a big city — you can have all of that and still feel like aging is unavoidable.

You share so much juicy info about Jean, Weight Watchers, and the weight-loss industry in general — stuff I’ve never heard before, and I’ve devoured a crap-ton of women’s magazines since I was a pre-teen. How much time did you spend on research for This Is Big?

I gave myself about a year to do the research. I kept a journal of my experience doing Weight Watchers, and took notes about the meetings and my thoughts. I also went to the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library and studied everything pertaining to Weight Watchers and dieting. I interviewed an expert at the Heinz Corporation. I interviewed people who knew Jean and read tons of archival information, magazine articles, and Weight Watchers magazine stories, and watched TV shows featuring Jean. I read vintage cookbooks and talked to cooking experts — I cast a wide net. I never regret interviewing someone. I tried to do as much as possible so I could have an informed biography.

“Jean was kind of a fabulist, so you have to take some of what she said with a grain of salt. Jean had an over-the-top way of talking about her life, and I wanted to fact-check as much as I could.”

Jean was kind of a fabulist, so you have to take some of what she said with a grain of salt. Jean had an over-the-top way of talking about her life, and I wanted to fact-check as much as I could.

What do you hope people take away from reading This Is Big?

I hope they think a lot about what dieting really means to them. Dieting is shorthand for transformation — what are you really talking about when you say you want to lose 20, 50, or 100 pounds? How do you want your life to change and to what degree are you willing to go to do it? Who do you want to be in the end?

I hope readers realize it’s really hard to give up a certain desire to consume things. Maybe you’re going to diet yourself away from yourself, but it may come out in different ways — think about what you consume, whether it’s food or, say, time on the internet.

You’re very open about how dieting is all-consuming — you think about food all the time. How do you feel now that you’ve poured your heart out — are you more at peace with yourself?

I’m never at peace. I’m not a peaceful person; I’m never satisfied with myself or anything. I accept that I can be kind of proud of myself and also dissatisfied all the time. Because of the ulcer, I had to cut out a lot of foods — which was so different from dieting just to lose weight. Changing foods to prevent pain has been interesting — that has been interesting and much easier to do and have much resistance to it.

I come to you a year and a half after starting to write the book as pretty much the same person. I’ve made progress in some ways, but food really frustrates me. Sometimes I see a person in a bikini and feel jealous but also good about who I am and proud of the work I do.

It’s a fine line about feeling at peace. I’m also really driven and ambitious. It’s hard to imagine myself being any other way. I have a certain amount of desire to be better, and I’d like to eliminate the desire to be the best.

I’m grateful that you wrote about using drugs as a teen. You wrote, “The only time I’ve ever been thin—indisputably thin, in the way I’ve always dreamed of—was for a few short years in high school. This was achieved primarily through starvation eased by drugs.” How did you “coach” yourself to open up about using cocaine, methamphetamine, and other drugs?

It was more of a process of elimination. I was starting the writing just in journals and in notes on my phone, wherever I could record them, as the year was going on. By nature, those journals and notes were intimate and honest. Once I started outlining the book and writing, I took a lot of those initial passages and, of course, didn’t want it to sound like a diary entry, so there was polishing. There was still this rawness and honesty that remained that felt right for the book. The book wouldn’t work if there was any coyness or reluctance to be totally honest. I think it would be plain as day to the reader and to myself.

I’m a methodical planner when it comes to making my deadlines. I broke my ankle the week I was about to start writing the book in earnest, and was housebound. I live in a third-floor walk-up apartment in Brooklyn, so using crutches to get down the stairs was out of the question. In order to leave my building, I scooted down on my bottom. Luckily, in New York so many things can be delivered. I was really alone in August when so many people leave town.

I started writing the book in a vacuum space that felt separate from the world, which was good because a sort of intimacy and vulnerability were really in step with how I was feeling. I thought I could change certain things in the next draft, but once my editor and my team read it, they were so moved by the honesty, I knew I had to get over any fear and leave the feelings in.

You wrote “Denial, particularly self-denial, is its own kind of pleasure” among other psychological insights. Where does your emotional intelligence come from?

I’ve been in therapy for most of my life. Reflecting on myself and the world comes pretty naturally to me. As a Cancer, it’s my astrological birthright. I might liken it to my body. I’m really good at styling and dressing other people; a part of that is looking at other people’s bodies that I don’t have. I’ll be like, “I’m working with the whole rainbow here. This person doesn’t have this thing they hate about themselves.” It’s easy for me to dress other people.

I’ve learned how to dress myself without having so many reservations about myself. I’ve spent much of my life feeling ambivalent about my body and guilty and ashamed and also trying to be proud of it and trying to ignore it. All of these emotions are really normal to me. I’m pretty attuned to how emotions feel for other people.

I think a lot about how the world treats me and how the world treats other people. I’ve been treated unkindly by other people because of my body, but I also realize that I’m a white woman who hasn’t had to overcome much adversity. I definitely use myself as a baseline. I remind myself that if things are hard for me, what if I was a size 30 and not a 14? I think about how much harder the world must be for other people and try to understand how other people feel. It helps me understand some of the issues with size and helps me explain that to people.

You wrote that you were looking for a group to talk about emotions, something that you couldn’t instantly find in Weight Watchers groups. Why do you think the older generations were less interested in talking about their emotions than younger people?

In the book, I was talking about the first Weight Watchers group that I went to, which was charmingly old-school. I knew it wasn’t for me. I need more of an emotional connection. The women in that group were probably older boomers and the greatest generation. Maybe it’s the way they were raised to understand food and dieting — “you shouldn’t eat this.” I was interested in something more touchy-feely. I wanted to understand that people were feeling the same as I was. I wasn’t interested in talking about a smoothie recipe with one Weight Watchers point.

How do you feel about being in your 40s — what do you like and dislike?

I used to fantasize about what my exciting adult life would be like — maybe really rich or living with a super hot husband. I used to feel like sky is the limit, but once you get to a certain age, it’s like, “Oh, this is my life.”

In our 40s, we’re not waiting for life to begin anymore — there’s something that can be a little sobering and a little dreary about that. And I say that as someone who goes on awesome vacations all the time.

As for the good parts of my 40s, I feel more comfortable with myself and what I want, and everything is more sharply in focus. When I turned 40, I realized that I’m too old for this shit for certain things. Like, I’m 40 fucking years old — I’m not dealing with this person. For certain things, it’s become easier to trim the fat, so to speak.

As I get older, I’ve become happier about my decision not to have children. Some of my friends have kids and I love them and enjoy buying them lavish stuff and taking them to musicals. Every year I go on a sailing trip — people in their 40s and their kids; we’ve made good choices to get here.